During a search of Penelope Harris’s Bronx apartment in 2010, police found 10 grams of cannabis. Even in the days before cannabis legalization in New York, that tiny amount fell below the legal threshold for a misdemeanor, according to The New York Times.

But that brief interaction with the police, which resulted in no criminal charges against Harris, spiraled into disastrous consequences for her and her family. Acting on a referral from police, the child welfare system—which some advocates insist is more accurately termed “the family policing system”—removed Harris’s son from her custody and placed him in foster care. The agency investigated her for neglect, and only returned her son on the condition that she agree to random drug screenings and unannounced caseworker visits.

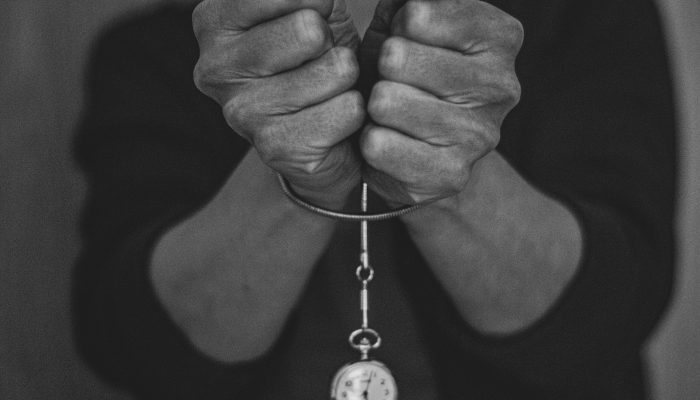

Harris’s case illustrates how even minor interactions with the legal system can have far-reaching impact. Punishment often does not end at conviction and sentencing. Instead, the consequences of a history with the legal system can spill over into people’s lives for years, or decades—long after their cases have been closed or they’ve completed their sentences. These harms are commonly referred to as “collateral consequences”—a euphemism which masks the dire situations that formerly incarcerated people face and that disproportionately impact Black people and other people of color.

Here’s what those “collateral consequences” can look like in practice:

Family separation

As Harris’s case demonstrates, parents who have interactions with the police or legal system—even those that do not lead to a conviction—may be subject to surveillance and the threat of losing their children. “So many parents come to our family defense practice terrified that their kids are going to be taken away because of minor police interactions that, for many other people, wouldn’t involve any additional follow up,” said Alice Fontier, managing director of Neighborhood Defender Service of Harlem, a public defender office which represents parents in family defense cases. “For our clients, mostly Black parents, those same interactions often mean an enormous amount of surveillance by [child welfare agencies], all under threat that their family could be torn apart.”

Once a child welfare agency initiates an investigation, a parent comes under intense scrutiny. With the agency’s advice, courts can mandate different sorts of requirements, like drug testing, random child welfare visits, and legal appearances. In New York City, the Administration for Children’s Services (ACS) can also initiate “emergency removals” that wrest children from their homes. A finding of neglect, the most common reason child welfare agencies remove children from their homes, can stem from an accusation as innocuous as a messy home or a broken smoke detector.

Because child welfare systems are deeply connected to broader racial injustice in the criminal legal system, enforcement is felt differently across race and class. One study found that California’s child protective agency had investigated half of all Black and Indigenous children born in the state in 1999 by the time they reached adulthood. In New York, an internal ACS study found that Black families were seven times more likely to be investigated and 13 times more likely to have their children removed than white families. ACS initiates investigations in districts with the highest child poverty rates four times more often than in those with the lowest.

Unemployment and loss of income

Any interaction with the legal system can have disastrous consequences on someone’s ability to earn a living. Incarceration for any duration can lead to missing work and potentially losing employment altogether. Even a misdemeanor conviction can lead to a 16 percent loss of income every year. A prison stint drops someone’s subsequent earnings by an average of 52 percent annually. Those figures can represent hundreds of thousands of dollars in lost income.

You can read the full article at Vera.